Introduction — In the practice of the Buddha-Dharma, it can be helpful to cultivate and practice certain positive attitudes of mind, e.g. respect, gratitude, patience, willingness, openness, generosity, humility, trust, etc. These attitudes of mind are essential for any spiritual practice, and are indeed aspects of our Unborn True nature. Unfortunately, in my experience, many people feel uncomfortable encouraging within themselves some or all of these attitudes of mind, for whatever reasons. One of our practices that, with time, can begin to change this discomfort is bowing. A bow can express the True Heart that connects us all in a very natural way. In fact, in our particular tradition, there is a saying that, “While bowing lasts, Buddhism will last.” The simple, physical practice of bowing somehow loosens our aversion to opening ourselves to those attitudes of mind. It may take a while, perhaps a long while, for us to begin to feel more comfortable with them, but bowing helps.

Gassho

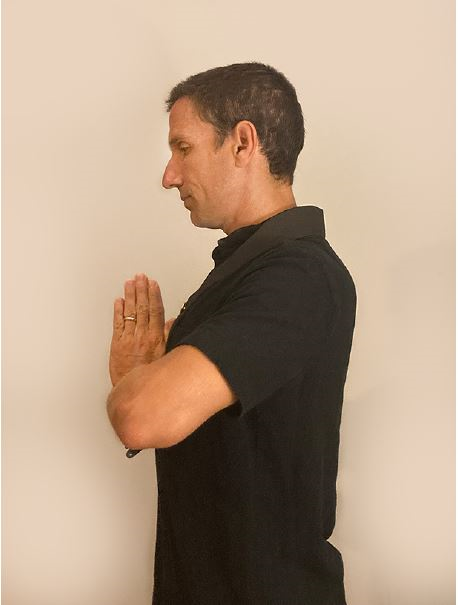

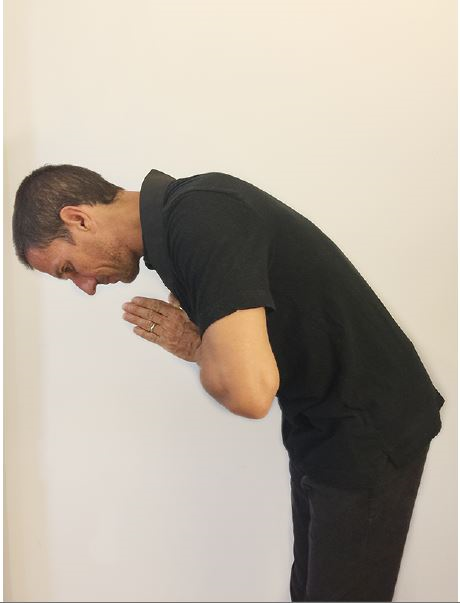

Description — An integral part of our bowing in the OBC is a simple, prayer-like gesture called, in Japanese, a “gasshō.” The Wiktionary says that the translation is “Buddhist-style pressed-palm gesture of piety,” from Middle Chinese “unite” and “palm,” and it is both a noun and a verb. So the gesture is made, sitting or standing with our feet together, pressing our palms together in front of our chest, with the elbows away from our sides, the arms level, and no space between our hands, our fingers, or our fingers and thumbs. The fingers point straight up with our thumbs touching our chest — see photos. This should be done brightly and energetically, but without tension. We often combine this gesture with a simple bow from the waist — from the hips really — with a straight back. This gassho with upper body bow is called a “monjin,” also both a noun and a verb — see photos.

Gasshō

Gasshō

Monjin

Don’t, however, let the ideal get in the way of your training. These forms can be very helpful when used with the right attitude of mind — in fact, in inspiring the right attitude of mind — but if you are unable, for some reason, to match them, don’t worry about it. I am knock-kneed, and I also have difficulty with balance, so I have some problems with standing with my feet together. I simply do the best that I can. That is enough.

Explanation — This simple gesture, this gassho, is a physical manifestation of our practice. We are bringing together the opposites to discover a third position beyond them, finding the unity of the opposites. If you can imagine one hand being “I like” and the other being “I don’t like”; one hand being “I want,” and the other being “I don’t want”; one hand being “she’s good,” and the other being “he’s bad”; one hand being “chocolate’s good,” and the other being “broccoli is bad,” then your practice is to bring these opposites together to sit still in the midst of them, to let them go, to not be controlled by them. You are letting go of your opinions, of your judgments. Every time you make this gesture, and in our practice you make it often, you have an opportunity to remind yourself to let go of your judgments and your opinions, to stop being controlled by them. I am not suggesting that you become passive or indifferent. You still recognize that some things are helpful and others are not, but you do not need to judge, to be attached. This is one of the important lessons of the gassho.

Another dimension of the gassho is as a respectful greeting to other beings, especially those who are training in Buddhism. Properly used, it is a recognition of the Buddha Nature in all. It is also a gesture of reverence and sincerity. It is the gesture by which the Buddha’s followers greeted the Buddha.

Additionally, it is a gesture of gratitude, which we can make when we receive something — or give something. We can also make it to open ourselves to looking up; to asking for help; or when we recognize how fortunate we truly are. By physically making this gesture we can open ourselves to the experience, as well as the expression, of gratitude.

Ceremonial — Before sitting down to meditate, we use this gesture as we make monjin to our seat, then, turning 180° to the right, when we make monjin to the world, or to those sharing our meditation practice, and to the space which affords us a place to sit. Even when sitting alone, we can still bow “to others” before and after sitting, thus recognizing that we train for both ourselves and others and that we are grateful for the training of others. We make seated monjin at the formal beginning of meditation when the gong rings three times; at the formal end of meditation following the gong ringing twice; and, after standing, again to our seat and to others sharing our practice. We also use this gesture when entering or leaving the meditation hall, and if we should pass in front of an altar. We begin and end full bows in gassho, and ideally remain upright and in gassho as we go from standing to kneeling and when arising from our knees.

Commentary — Rev. Master Daizui MacPhillamy, the second Head of our Order said: “The gasshō is excellent to help unify and calm the body and mind when one has become scattered or distracted. The use of this mudra, even for an instant, can break the hold of seemingly frantic circumstances and give one a fresh perspective. Thus in a Zen temple you will see people making the mudra of gasshō not only to each other and to the Buddha statue and the Scriptures, but also to their work, their food, the mistakes they have just made, and in any situation where it is good to collect oneself in a state of single-mindedness and reverence.”

Bowing

Description — To make a full bow, we stand facing in the direction of the altar, with our feet together and our hands in gassho. Ideally, while continuing in gassho, we then gracefully kneel, sitting back on our heels — see photos. In unison with everyone else with whom we are sharing these bows, and following the lead of the celebrant, we then lean forward, touching our forehead to the floor, with our forearms parallel to each other, touching the floor on either side of our head, with our hands open and palms upward. Allowing our elbows to continue touching the floor, we gently lift our hands above our heads, palms upward, symbolizing raising the feet of the Buddha above our own head — see photos. I think of this gesture as an offering. We thus make an offering of our training and symbolize the opening of the lotus blossom. We then lower our hands, and sit back up, returning to gassho, and ideally, continuing to rise with a graceful, flowing motion, raising our body to stand upright again, in gassho, continuing to keep our feet together.

coming to full bow

full bow

Ceremonial — We tend to do these bows in triplets, i.e. for the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, while facing in the direction of the altar or each other. We recite one of the Three Refuges silently to ourselves as we raise our hands in offering during each bow. We will bow multiple times during a service.

Commentary — The Buddha on the altar embodies the Best in ourselves, so. bowing to it is recognizing Something within ourselves. Also, bowing subtly nourishes those aforementioned attitudes in our hearts, perhaps in spite of ourselves. It is a natural, physical expression of humility, patience, gratitude, reverence, etc. It is one of the central aspects of our practice, and shouldn’t be undervalued, or belittled. Also, be aware that supporting the Buddha, while raising his feet above our heads, emphasizes our humility and gratitude, while at the same time, illustrating that our training supports the Buddha-Dharma. However we may feel about any of these aspects of bowing, if we persevere, they will have subtle, but profound and unexpected effects on our lives.

| Rev. Master Rokuzan | February, 2025 | Columbia Zen Buddhist Priory |

|---|